Desmond Mountjoy

When it comes to Stid, it’s hard to compete with the beautiful tribute written in “The Melody of God”. I don’t have a copy but about 20 years ago I sat at my Grandmother’s kitchen table and wrote it out long-hand on her writing paper.

Apparently, it’s now available as a reprint

http://www.fishpond.com.au/Books/Melody-of-God-Desmond-Mountjoy/9781331377283

so we’ll be checking that out. In the meantime, here are some excerpts:

I never heard him talk of heroes or of being a hero, or longing for chances of undertaking heroic stunts. Yet when the opportunity came to inspire his men at a critical moment, he instinctively took it.”

“The Melody of God and other papers” by Desmond Mountjoy. Constable & Company. London * Bombay * Sydney 1923

The following was transcribed from the manuscript which may differ from the published version.

STID: An Australian Soldier Boy.

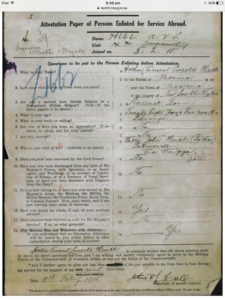

A rush to Waterloo Station to catch the early afternoon express to Salisbury after a tiresome morning spent at the War Office conference. As I hastened up the platform I was greeted by a sturdy, lithe Australian soldier with the largest, fattest and most friendly of smiles. A very sunburned face, clean shaved like all Australians, an extraordinarily fine set of white teeth, dusky hair and frank eyes the colour of a jade green sea; eyes that had looked long on sun-drenched far horizons and captured and kept their beauty and their truth- all this made up an unforgettable picture of happy friendliness. In the course of my job I met hundreds of officers every week and had more than once met practically every officer in the third Australian Division then on Salisbury Plain, but who this particular one was I had not the faintest notion, though evidently he knew me. The purple and green shaped diamond badge on his shoulder said eighteenth Battalion, but at that time that Battalion was with the Second Australian Division in France.

We talked all the way and long before we reached Andover where he had to get out for Perham Down Camp I knew all about him, who he was and where we had met before. In addition I had obtained a complete account of his career as a cadet at Oxford and a glimpse into his home life in far away New South Wales.

From that moment our relations were perfect requiring no subsequent explanation or adjustment. It was another of those quick, close friendships of war, so impossible to anticipate, so difficult to explain or even personally to realise and believe in now that the tragic circumstances which made them possible are gone like a hideous dream.

We did not part, you may be sure without arranging an early meeting and as I waved to him standing on the platform the sun seemed to me to have set for the day.

A few days later I met him again as arranged.

I found this backwoods boy knew and loved literature and animals and had a passionate love for nature in all her moods. As we talked our immediate surroundings disappeared and we were together in New South Wales. I saw the loved homestead where his parents, brothers and sisters dwelt, the little farm not very far away which was “his very Own.” He said “I can see the very earliest signs of the springing corn (wheat??) I can see it rise in little green waves that mean so much to me.” Then there was the mountain that he loved.

The darkness crept on; the hot stuffy air of the old cathedral city was cooled by deep waves of deep waves from Australia; great stars burned low above us; endless spaces stretched around us and khaki uniforms and the reasons why we wore them seemed the most unreal of things- unreal, unbelievable, meaningless!

Stid spoke of home, of France and happy hours there with his best beloved comrade, Little Jim.

It was at the Signal Depot, Liverpool Camp in Australia and Jim was getting through his first day in the elementary squad. He was clumsily practising figure eight when he was offered help by Stid who,from the wide experience gained by a whole week at signalling, felt he must help a newcomer. Jim thought Stid at the time the kindest chap he had ever met and from that moment the two became friends. They walked in the bush together, talked and talked, went to town, visited Stid’s Little Aunt at Mangrove Mountain. The link was only broken – that is if it was broken – by death.

Egypt, Anzac Cove, (at Hill 60 their section had 5 men left out of 20) – Armentieres, Ypres- I heard it all. Then inspired by the peace around us we turned once more to our books.

It was there and then that I tried him high, higher than I had dared to try many of my admittedly literary friends. Taking upon of the most beautiful, human, true and understanding books that appeared in my time I read aloud…

The Australian soldier boy who instinctively recognised the great truth and beauty of these passages thereby proved his kinship with the elect: he understood the meaning of beauty, sorrow, sin and life and understanding was as unafraid of them as he was of death.

The day before he left Tidworth for France he arrived in Salisbury in the afternoon. We took a walk around the Close after tea and looked at the cathedral from every point of view. It was a glorious August afternoon. Did a little shopping and looked at one or two favourite spots in the old city. The imminent parting cast its shadow yet we were not sad. After dinner we sat quietly talking in the twilight but not as might be thought of particularly serious things. Of course at times we talked about the war…

Stid was as cheerful as ever, and had we been able to completely ignore the fact that it was our last meeting at Salisbury we would have been perfectly content.

On the other hand there was much to look forward to in France. There was the war – which he loved, the return to his Battalion and all his friends there. Above all there was once more the longed for return of the old days when he fought side by side with his best beloved comrade, Little Jim. So I helped him put his kit together as we talked into the night.

The next morning we were up early, stuck our heads out our windows looked down High Street to the Cathedral Gate for the last time.

Breakfast and a quick run out to Tidworth Station where we deposited his kit against his departure at noon for Southhampton in command of a party of men. Then to camp where I handed him over in good time to the Commandant. In the presence of many others the last handclasp and the last casual-looking good-bye.

I had very few letters from him in France as he went out early in August and was killed early in October (9th) at Passchendale. Those I did receive were about his work and his men, both of which he passionately loved. He was very humble minded and always trying to improve himself.

It is almost impertinent to say he died gallantly. Mr. A. Pearse, the official Australian war artist painted a striking picture entitled “The Battle of Polygon Wood.” It was extensively reproduced and was accepted by all Australians as a typical incident in one of their uncountable engagements.

He was killed three weeks later.

He was a typical Australian soldier boy.

He was as sincere and direct as sunlight and unpretentious as a wayside flower. I never heard him talk of heroes or of being a hero or longing for chances of undertaking heroic stunts, yet when the opportunity came to inspire his men at the critical moment he instinctively took it.

There was a job wanted doing and he was there to do his best and ever did it smilingly.

He sleeps somewhere in France. (Even now we don’t know where)* and away yonder in Australia the “little farm” is vacant and he climbs no more to the windmill toot see how grows the corn. (wheat?).

He is ever to us a fragrant memory, a quenchless inspiration, a reward for what we have endured. A pledge that however lonely here, we shall no longer be alone when like him we too “Go West.”